Go Ahead, Blame Twitter

How sharing memes may be keeping us apart

BY FRED SANDSMARK ’83 PHOTOGRAPHY BY GARVIN TSO

Associate Professor Grant Kien studies very small things that grow and mutate and propagate.

He observes them as they spread around the world, and tries to understand how and why they behave as they do.

But he’s not a biologist peering through a microscope or an epidemiologist tracking a disease outbreak. Kien is an associate professor in Cal State East Bay’s Department of Communication, and his subject is Internet memes.

Yes, memes.

And not just the pictures with sarcastic captions.

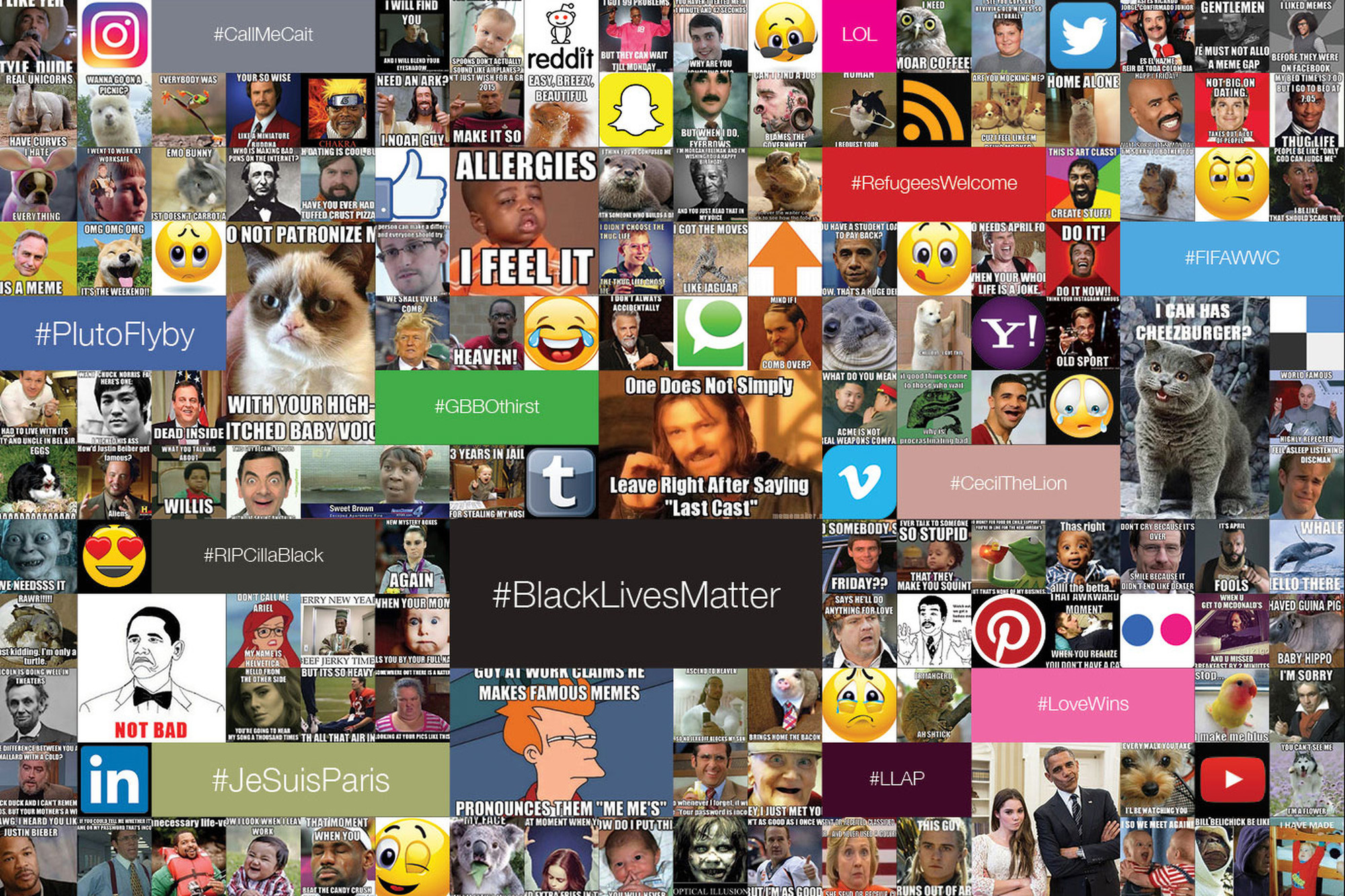

Memes, by definition, encompass any image, video or piece of text that can “go viral” across the Internet — the low-budget videos, celebrity GIFs and hashtags that fill our social media feeds and generate countless shares, comments and emoticons.

Silly, you might think, but Kien argues that memes deserve rigorous academic analysis because they are a major way in which people today express vital thoughts and ideas — about themselves, each other and the world we live in.

Take just a few of Twitter’s “Most famous hashtags of 2015”: #RefugeesWelcome, #PlutoFlyby, #FIFAWWC, #JeSuisParis, #CaitlynJenner and so on. In just three words or less, they distill contemporary thought and emotion surrounding politics, terrorism, science, popular culture, social movement — and some of the most pivotal events of the 21st century thus far.

Even more important, Kien says, memes need to be understood because they can spread beyond digital networks to affect the physical world: Just think of #BlackLivesMatter — it’s a social movement that has spread across the country and began entirely online.

But the impact of most memes is subtle. While memes certainly can be funny and lighthearted, the professor says they play a critical role in “hipster racism” — the ironic sharing of humor based on race, disability, religion, sex and other attributes.

“These are intended to be jokes between knowing people, and quite often that’s how they’re consumed,” Kien explains.

But because the Internet is a broadcast medium, the messages sometimes take on lives of their own.

“When we’re mindlessly reposting, resharing and upvoting (hitting the “thumbs up” button on a post), we’re actually propagating the very same social ills that we’ve been fighting so hard to eradicate offline,” Kien says.

Whether these actions take the form of spreading images of “Hitler Kitty” (a cat with markings that mimic Adolph Hitler’s mustache) or sharing the video of a bus driver bullied by elementary school passengers, memes have the power, for example, to collectively minimize a horrific and violent tragedy, or amass $700,000 in donations from sympathetic viewers.

In the context of our election-year politics and the rampant spread of memes that comment on presidential candidates and bipartisan views, keeping a shrewd eye on social media will be vital. Because intentionally or not, Kien says, our social media–saturated culture is increasingly serving to isolate and divide us.

“We’re uniting around things based on how we feel about them, not how we think about them.”

Graduate student Amalia Alexandru is doing the research to prove it.

For her master’s thesis in communication, Alexandru analyzed Twitter messages from the 2013 two-week federal government shutdown. “It is interesting to see how politics has adopted social media and merged old (communication) tactics with new tools and strategies,” she says. “Memes are a vital way (for political parties) to connect with specific groups within the masses.”

Although Alexandru began with the premise that “politics, technology and culture in online platforms accommodate new waves of political perspectives,” her in-depth case study showed that messages on Twitter exist in silos, pitting groups against each other to evoke a binary, for-us-or-against-us emotional response — not to build relationships between entities and ideas or facilitate compromise.

“My generation is the generation that not only experienced the first wave of social media interaction, but also tested some of its implications,” she says. “Not being aware of the messaging behind social media and memes is a critical matter for future generations.”

“We’re uniting around things based on how we feel about them, not how we think about them,” Kien says. “I believe we have an ethical responsibility in this day and age to consider the very real impact this communication is having on the world, and to arm our students with the ability to dissect how those messages are shaping it.”

A MEME IN TIME: A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE EVOLUTION OF VIRAL MEDIA

Provided by Associate Professor Grant Kien

1941: Winston Churchill’s “V for Victory” is imitated by prominent figures such as Charles de Gaulle and Richard Nixon, ushering in the first era of memes. The meaning is reassigned by antiwar protesters in the 1960s and 1970s to signify peace, and in 1972, U.S. Olympic figure skater Janet Lynn sets off a wave of Asian assimilation when she is broadcast cheerfully flashing the sign after falling on the ice in Japan. The meme is so thoroughly adopted throughout Asia that it is now synonymous with Japanese, Chinese and Korean culture.

1941: Winston Churchill’s “V for Victory” is imitated by prominent figures such as Charles de Gaulle and Richard Nixon, ushering in the first era of memes. The meaning is reassigned by antiwar protesters in the 1960s and 1970s to signify peace, and in 1972, U.S. Olympic figure skater Janet Lynn sets off a wave of Asian assimilation when she is broadcast cheerfully flashing the sign after falling on the ice in Japan. The meme is so thoroughly adopted throughout Asia that it is now synonymous with Japanese, Chinese and Korean culture.

1969: The first Internet message (“LOGIN”) is sent between UCLA and Stanford; the fledgling network system crashes after the first two letters yet proves its potential.

1976: In his book “The Selfish Gene,” Richard Dawkins coins the term “meme” (from the Greek “mimeme,” meaning something imitated), describing it as, “Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain.”

1980s: Scientists and researchers share data and information on a global scale for the first time through ARPAnet, named for the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency. Simultaneously, various cultural phenomena lay the groundwork for memes in the age of social media: Hip-hop popularizes the concept of “mashups,” and “leetspeak” is born among hackers who use American Standard Code for Information Exchange (ASCII) as an “elite” language — preceding abbreviations like “LOL,” “OMG” and ultimately, emoticons.

1991: Tim Berners-Lee introduces an internet that is a “web” of public, retrievable information. The same year, the first traceable meme goes viral in the form of a mistranslated Japanese Sega Genesis video game ad.

1991: Tim Berners-Lee introduces an internet that is a “web” of public, retrievable information. The same year, the first traceable meme goes viral in the form of a mistranslated Japanese Sega Genesis video game ad.

1992: Students and researchers at the University of Illinois develop a browser that allows users to see words and pictures at the same, and to navigate information using scrollbars and clickable links. Congress approves use of the Internet for commercial purposes.

1994: Douglas Rushkoff publishes “Media Virus! Hidden Agendas in Popular Culture,” explaining how free email services like Hotmail and Yahoo! add advertising to outgoing messages. The book touches off a revolution in viral advertising.

1996: “Dancing Baby,” or “Baby Cha-Cha,” becomes one of the first bona fide internet memes through email forwards — and then leaps offline through a series of recurring hallucinations on the TV series “Ally McBeal.”

1996: “Dancing Baby,” or “Baby Cha-Cha,” becomes one of the first bona fide internet memes through email forwards — and then leaps offline through a series of recurring hallucinations on the TV series “Ally McBeal.”

2000s: Internet memes become a popular form of mediated communication between friends on social media networks, creating sensations such as “Star Wars Ninja Kid”; “Leeroy Jenkins”; “I Can Has Cheezburger Cat”; and countless others.

2003: MySpace launches. Its large population of musicians and fans leads to the embedding of music and video players into MySpace pages, popularizing what become known as internet mashups — web applications that combine functionality from more than one online media source.

2005: The Reddit.com community web platform goes live with its user upvote system that ranks user-submitted content. Calling itself “the front page of the internet,” Reddit becomes one of the key sites propagating internet memes.

2006: Facebook debuts to the general public and quickly surpasses MySpace as the most popular social media platform. Building on MySpace’s mashups, it integrates wave after wave of rising social media platforms, such as Instagram, Twitter and YouTube, facilitating an enormous surge in viral activity. The same year, blogger Carmen Sognonvi coins the term “hipster racism” to describe the use of racist jokes and slurs and/or the misappropriation of cultural symbols “ironically,” and frequently through memes.

2013: After the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black 17-year-old in Sanford, Florida, three women communicating on social media claim #BlackLivesMatter as an expression of outrage against racial profiling of and police brutality toward African-Americans. Since going viral, #BlackLivesMatter has spawned a robust activist movement and international network.

2013: After the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed black 17-year-old in Sanford, Florida, three women communicating on social media claim #BlackLivesMatter as an expression of outrage against racial profiling of and police brutality toward African-Americans. Since going viral, #BlackLivesMatter has spawned a robust activist movement and international network.